How abstraction could change the look of the Metaverse

Simon Husslein

The oncoming Metaverse has been described as a gateway, crossing the physical and digital divide between actual and virtual realities. It has been predicted that we will spend an increasing amount of time of our lives inside digital spaces, creating memories that will extend physical experiences in scope, meaning, and value. This shift will include a transition from defining spaces based on physical borders to new concepts of what we will recognize as a ‘place’ and it offers a unique opportunity for architects and designers alike to articulate new archetypes of spatial awareness.

A room is commonly defined by an area within a building that has its own walls, floor, and ceiling. This arrangement is mostly related to physical conditions and the history of interiors. Digital spaces currently mimic known archetypes of physically built architecture in various forms while imitating the behavior of its material surfaces and of its light conditions. If current trends continue, it won't be too long until these simulations will reach a point when it will be difficult to visually distinguish actual from virtual environments. It seems that visual and also auditory simulations are comparatively easy to conduct. The climatic conditions of a room, however, are not easily simulated. But they are playing a significant role in how we perceive our environment. These conditions include smell, room temperature, humidity, concentration of oxygen, air movement, or the emission of heat or coldness from nearby materials. The technological challenges to simulate such complexity seem very hard to overcome. This might lead to an increasing problem when spending an extended amount of time inside simulations of architectural inspired spaces. While the visual projections get more and more convincing, the lack of a holistic spatial perception on the other side, might lead to an uncanny feeling. Some visitors of current digital spaces have described an unpleasant mismatch between what they see and what they feel. These challenges might not be a substantial problem for some of the immersive experiences such as gaming, predictive simulation, or exploration of digital realms. But spending an increasing amount of time inside virtual environments for use cases such as education, training, meeting, content creation or relaxation most likely won’t be the ideal experience for many inhabitants. This raises the question if virtual spaces, that purposely use alternative typologies, are capable of offering a better solution. In the following I will introduce early concepts of ‘genuine virtual spaces’ beyond the visual vocabulary of physical representation.

Genuine Virtual Spaces

Versions of virtual reality spaces without relations to architecture can already be found in existing VR applications. A common typology is a kind of ‘void’, an environment without visual boundaries, mostly presented in the colors white or black with a grid representing a ‘floor’ for spatial orientation. These minimalistic spaces seem to be a straight-forward solution as there is no distraction inside the visible realm. But the reality of spending time inside such empty environments seems a stretch too far. Users have described their presence inside empty VR spaces as ‘feeling lost’. This may be related to the lack of detail and visual stimuli, making a shift beyond what seems to be pleasant. Therefore, a ‘void’ might just represent a placeholder for more sophisticated atmospheric solutions to come.

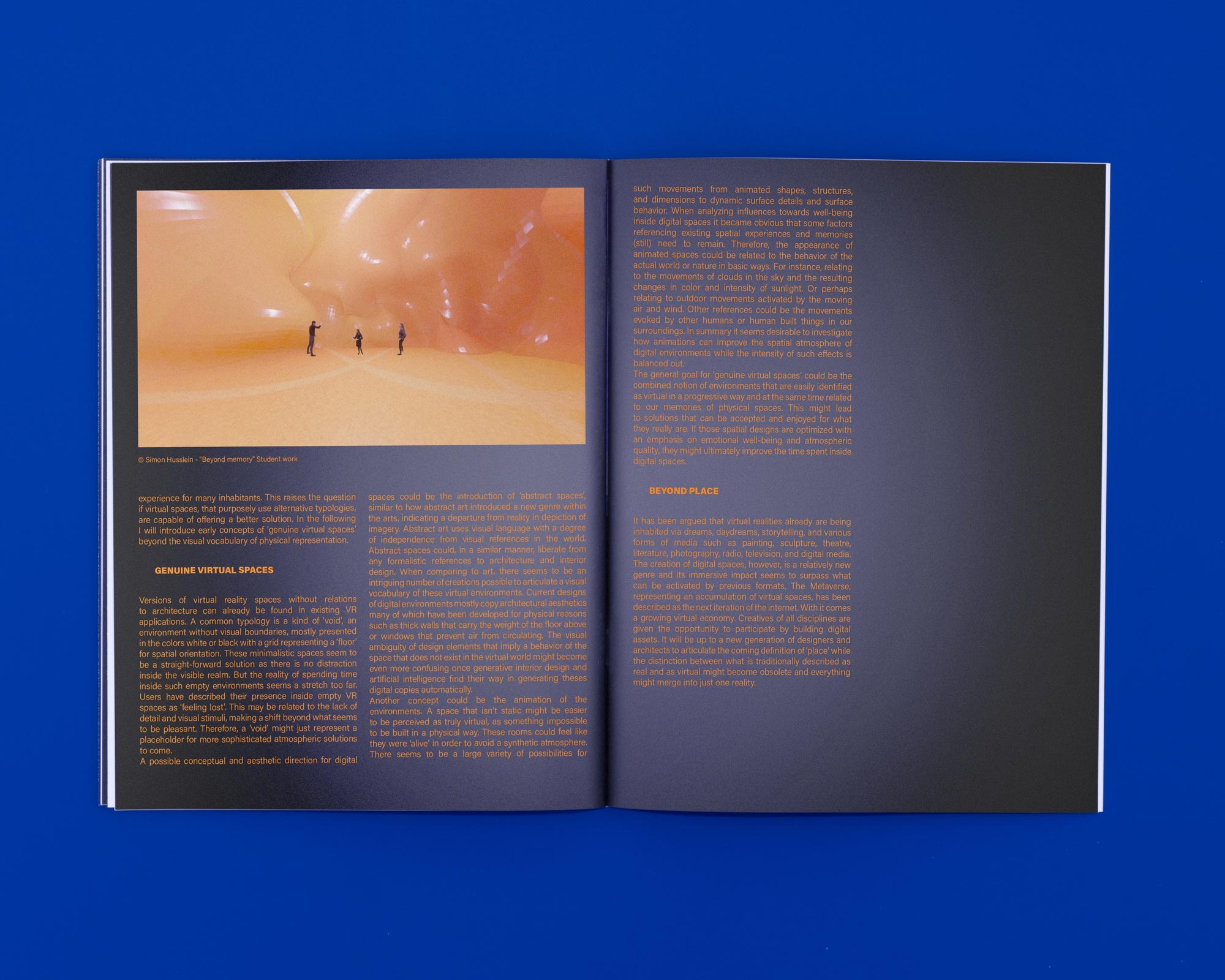

A possible conceptual and aesthetic direction for digital spaces could be the introduction of ‘abstract spaces’, similar to how abstract art introduced a new genre within the arts, indicating a departure from reality in depiction of imagery. Abstract art uses visual language with a degree of independence from visual references in the world. Abstract spaces could, in a similar manner, liberate from any formalistic references to architecture and interior design. When comparing to art, there seems to be an intriguing number of creations possible to articulate a visual vocabulary of these virtual environments. Current designs of digital environments mostly copy architectural aesthetics many of which have been developed for physical reasons such as thick walls that carry the weight of the floor above or windows that prevent air from circulating. The visual ambiguity of design elements that imply a behavior of the space that does not exist in the virtual world might become even more confusing once generative interior design and artificial intelligence find their way in generating theses digital copies automatically.

Another concept could be the animation of the environments. A space that isn’t static might be easier to be perceived as truly virtual, something impossible to be built in a physical way. These rooms could feel like they were ‘alive’ in order to avoid a synthetic atmosphere. There seems to be a large variety of possibilities for such movements from animated shapes, structures, and dimensions to dynamic surface details and surface behavior. When analyzing influences towards well-being inside digital spaces it became obvious that some factors referencing existing spatial experiences and memories (still) need to remain. Therefore, the appearance of animated spaces could be related to the behavior of the actual world or nature in basic ways. For instance, relating to the movements of clouds in the sky and the resulting changes in color and intensity of sunlight. Or perhaps relating to outdoor movements activated by the moving air and wind. Other references could be the movements evoked by other humans or human built things in our surroundings. In summary it seems desirable to investigate how animations can improve the spatial atmosphere of digital environments while the intensity of such effects is balanced out.

The general goal for ‘genuine virtual spaces’ could be the combined notion of environments that are easily identified as virtual in a progressive way and at the same time related to our memories of physical spaces. This might lead to solutions that can be accepted and enjoyed for what they really are. If those spatial designs are optimized with an emphasis on emotional well-being and atmospheric quality, they might ultimately improve the time spent inside digital spaces.

Beyond Place

It has been argued that virtual realities already are being inhabited via dreams, daydreams, storytelling, and various forms of media such as painting, sculpture, theatre, literature, photography, radio, television, and digital media. The creation of digital spaces, however, is a relatively new genre and its immersive impact seems to surpass what can be activated by previous formats. The Metaverse, representing an accumulation of virtual spaces, has been described as the next iteration of the internet. With it comes a growing virtual economy. Creatives of all disciplines are given the opportunity to participate by building digital assets. It will be up to a new generation of designers and architects to articulate the coming definition of ‘place’ while the distinction between what is traditionally described as real and as virtual might become obsolete and everything might merge into just one reality.

The oncoming Metaverse has been described as a gateway, crossing the physical and digital divide between actual and virtual realities. It has been predicted that we will spend an increasing amount of time of our lives inside digital spaces, creating memories that will extend physical experiences in scope, meaning, and value. This shift will include a transition from defining spaces based on physical borders to new concepts of what we will recognize as a ‘place’ and it offers a unique opportunity for architects and designers alike to articulate new archetypes of spatial awareness.

A room is commonly defined by an area within a building that has its own walls, floor, and ceiling. This arrangement is mostly related to physical conditions and the history of interiors. Digital spaces currently mimic known archetypes of physically built architecture in various forms while imitating the behavior of its material surfaces and of its light conditions. If current trends continue, it won't be too long until these simulations will reach a point when it will be difficult to visually distinguish actual from virtual environments. It seems that visual and also auditory simulations are comparatively easy to conduct. The climatic conditions of a room, however, are not easily simulated. But they are playing a significant role in how we perceive our environment. These conditions include smell, room temperature, humidity, concentration of oxygen, air movement, or the emission of heat or coldness from nearby materials. The technological challenges to simulate such complexity seem very hard to overcome. This might lead to an increasing problem when spending an extended amount of time inside simulations of architectural inspired spaces. While the visual projections get more and more convincing, the lack of a holistic spatial perception on the other side, might lead to an uncanny feeling. Some visitors of current digital spaces have described an unpleasant mismatch between what they see and what they feel. These challenges might not be a substantial problem for some of the immersive experiences such as gaming, predictive simulation, or exploration of digital realms. But spending an increasing amount of time inside virtual environments for use cases such as education, training, meeting, content creation or relaxation most likely won’t be the ideal experience for many inhabitants. This raises the question if virtual spaces, that purposely use alternative typologies, are capable of offering a better solution. In the following I will introduce early concepts of ‘genuine virtual spaces’ beyond the visual vocabulary of physical representation.

Genuine Virtual Spaces

Versions of virtual reality spaces without relations to architecture can already be found in existing VR applications. A common typology is a kind of ‘void’, an environment without visual boundaries, mostly presented in the colors white or black with a grid representing a ‘floor’ for spatial orientation. These minimalistic spaces seem to be a straight-forward solution as there is no distraction inside the visible realm. But the reality of spending time inside such empty environments seems a stretch too far. Users have described their presence inside empty VR spaces as ‘feeling lost’. This may be related to the lack of detail and visual stimuli, making a shift beyond what seems to be pleasant. Therefore, a ‘void’ might just represent a placeholder for more sophisticated atmospheric solutions to come.

A possible conceptual and aesthetic direction for digital spaces could be the introduction of ‘abstract spaces’, similar to how abstract art introduced a new genre within the arts, indicating a departure from reality in depiction of imagery. Abstract art uses visual language with a degree of independence from visual references in the world. Abstract spaces could, in a similar manner, liberate from any formalistic references to architecture and interior design. When comparing to art, there seems to be an intriguing number of creations possible to articulate a visual vocabulary of these virtual environments. Current designs of digital environments mostly copy architectural aesthetics many of which have been developed for physical reasons such as thick walls that carry the weight of the floor above or windows that prevent air from circulating. The visual ambiguity of design elements that imply a behavior of the space that does not exist in the virtual world might become even more confusing once generative interior design and artificial intelligence find their way in generating theses digital copies automatically.

Another concept could be the animation of the environments. A space that isn’t static might be easier to be perceived as truly virtual, something impossible to be built in a physical way. These rooms could feel like they were ‘alive’ in order to avoid a synthetic atmosphere. There seems to be a large variety of possibilities for such movements from animated shapes, structures, and dimensions to dynamic surface details and surface behavior. When analyzing influences towards well-being inside digital spaces it became obvious that some factors referencing existing spatial experiences and memories (still) need to remain. Therefore, the appearance of animated spaces could be related to the behavior of the actual world or nature in basic ways. For instance, relating to the movements of clouds in the sky and the resulting changes in color and intensity of sunlight. Or perhaps relating to outdoor movements activated by the moving air and wind. Other references could be the movements evoked by other humans or human built things in our surroundings. In summary it seems desirable to investigate how animations can improve the spatial atmosphere of digital environments while the intensity of such effects is balanced out.

The general goal for ‘genuine virtual spaces’ could be the combined notion of environments that are easily identified as virtual in a progressive way and at the same time related to our memories of physical spaces. This might lead to solutions that can be accepted and enjoyed for what they really are. If those spatial designs are optimized with an emphasis on emotional well-being and atmospheric quality, they might ultimately improve the time spent inside digital spaces.

Beyond Place

It has been argued that virtual realities already are being inhabited via dreams, daydreams, storytelling, and various forms of media such as painting, sculpture, theatre, literature, photography, radio, television, and digital media. The creation of digital spaces, however, is a relatively new genre and its immersive impact seems to surpass what can be activated by previous formats. The Metaverse, representing an accumulation of virtual spaces, has been described as the next iteration of the internet. With it comes a growing virtual economy. Creatives of all disciplines are given the opportunity to participate by building digital assets. It will be up to a new generation of designers and architects to articulate the coming definition of ‘place’ while the distinction between what is traditionally described as real and as virtual might become obsolete and everything might merge into just one reality.

Published 2022 in ENTERING THE ROOM, a magazine conducted by students of the MAIA program. Part of the Interior Architectur Department at HEAD – Genève. In collaboration with Volume magazine.

Introduction | Editorial | References | Projects | Research

HEAD – Genève | Interior Architecture | Atelier Simon Husslein | Copyright © 2025